by Dean | Jul 26, 2017 | General

Straw Dogs (1971 film) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

I’m tired of contemporary Hollywood films that appear to have been scripted by young, liberal know-it-alls (example: Spider-Man: Homecoming). By no means is this the case with a Hollywood item from the past like Sam Peckinpah‘s Straw Dogs (1971), which I reviewed on this site once before. I said the film was not quite a success, but I demur from that now. It is an imperfect but serious and riveting thriller.

A “straw dog” is something that is made only to be destroyed. David (Dustin Hoffman) and Amy (Susan George) are trying to make a life for themselves in Amy’s Cornish village, but shiftless, lascivious rustics soon intend to destroy it. They clearly diss David the intellectual and envy his union with pretty Amy, who is sexually victimized by two of them. Although this has nothing to do with Amy’s not being a strong woman, it is indeed true that she is not strong (a notion the know-it-alls would refuse to brook) , but neither is David. They’re both very human. David is not manly enough until the last act, and he is imperceptive.

Straw Dogs is hard on the human race, which is, as critic John Simon has put it, “eager for compromise, wallowing in reciprocal abasement, and balking at accommodation only when denied even its widow’s mite.” A measure of sympathy, though, goes to the primary characters, to David and Amy, and it is also certain that screenwriters Peckinpah and David Zelag Goodman—the film is based on a novel by Gordon Williams—never pretend to have their understanding of these two persons all wrapped up. As the film runs its course, they constantly probe David and Amy for who they are, what they think, what they want. None of this has anything to do with ideology or intellectual stasis. It has to do with artistic acumen. Although it’s a shame that Dogs may have been Peckinpah’s last good film, at least genuinely young, Millennial-like minds were not behind it.

by Dean | Jul 24, 2017 | General

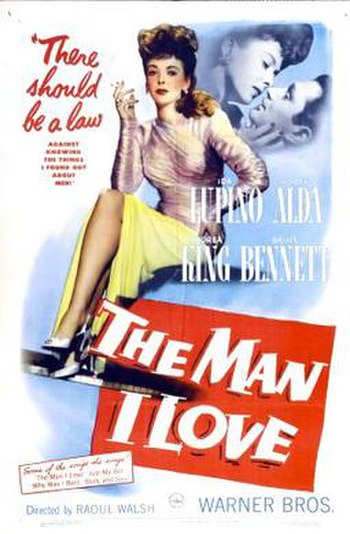

The Man I Love (film) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

In large measure Raoul Walsh‘s The Man I Love (1947) is about nightclub life, with a chunk of real shadiness tossed in. Ida Lupino stars as a tough-minded but amiable club singer, who doesn’t care much about her job since her boss (Robert Alda) is a cocky heel who makes advances to her. Alda ain’t the man she loves; really, the man she loves seems like a bore and is badly acted by Bruce Bennett. Lupino’s scenes with him are the weakest in the movie.

Other scenes, however, such as those with Petey Brown (Lupino) and her family, are spunky and agreeable. The movie in toto is agreeable, if without the greatest plot in the world.

by Dean | Jul 20, 2017 | General

Summer with Monika (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

A Summer with Monika (1953) is a Swedish film directed by Ingmar Bergman from a novel by Per Anders Fogelstrom.

Monika (Harriet Andersson), for a long time a believable character, and Harry (Lars Ekberg), not much explored, are two adolescent lovers. Both are inexperienced and foolish but also harassed and even mistreated. Eventually they marry, but in the film’s final third, unfortunately, Bergman allows Monika to become a surprising tramp. This is, nonetheless, one of the Swede’s few successful movies, remarkably made with its wonderful exterior shots, long takes and (of course) mise en scene.

In addition, it is a famously erotic film—and not just for 1953—albeit Andersson has assets other than those under her blouse. She is an actress so “natural” it is uncanny, as true in her hysteria as in everything else. She creates a good blending of sophistication and innocence, and is enticingly kinetic. It is a great performance in a more-than-okay movie.

(In Swedish with English subtitles)

by Dean | Jul 18, 2017 | General

Cover via Amazon

The commercial Western novels from earlier decades usually had their cowboy heroes fall in love with a young woman who had not yet married. The 1956 Western movie, Seven Men from Now—it too is commercial, of course—offers a hero with a sure liking for a young woman who is married, but he staunchly refuses to start anything. A man of principle, he is played by Randolph Scott, and the seven men of the title are the gold robbers who murdered Scott’s wife and are now being pursued by him.

‘Tis strange that Ben Stride, Scott’s character, doesn’t appear to be suffering much over his wife’s death, and neither does the aforementioned young woman (Gail Russell) seem devastated by the vile murder of her husband (Walter Reed). It’s as though the producers opposed any big-deal, negative emotion (and if they hadn’t, could Scott have delivered?).

All the same, this Budd Boetticher Western, written by Burt Kennedy, is dramatically piercing. A perfect, and not strident, performance comes from Lee Marvin with his big personality. Russell, Reed and others provide a handful of not-bad performances. . . In more ways than one, Seven Men is colorful, another ’50s picture proving how well literal color works for Westerns. Above all, it is just as entertaining as those Western novels from earlier decades—those I have read, anyway.

by Dean | Jul 17, 2017 | General

The novel The Dark Angels (1936), by Francois Mauriac, presents us with the complicated Gradere, a man who allows himself to sink into utterly foul illegality. A particular woman, Aline, is a threat to him because of Gradere’s dirty business practices, and an elderly man named Desbats uses her to deepen the threat. Gradere determines to do something about it.

The novel’s prologue consists of a letter Gradere has written to the village priest, Alain, a good man. The priest recoils passionately from some information in the letter: Gradere was once told by another priest that “there are human souls that have been given to [the Devil].” The reader is left to ask whether this is so. Mauriac seems to see a half-truth in it, but also expresses, of course, his Christian optimism about God, He Who is “greater than the strength of our mad desire to achieve damnation.” Withal, he brings Gradere to faith and repentance.

Frankly, this might be deemed implausible and even forced—it is not like the conclusion of, say, Read’s A Married Man—and yet it takes place at the same time that the priest is afflicted with a troubled, self-doubting mind. This seems to make Gradere’s conversion artistically acceptable. . . The Dark Angels is a wise and poetically written book. As for the title, well, if certain souls (or all souls?) are given to the Devil, maybe it is the “dark” angels, as it were, who effect it.