by Dean | Apr 12, 2018 | General

Christian women, like other women, chat about past gatherings with relatives, as on holidays. Obviously they mention mothers and fathers and grandparents and others who have passed on, liking the stories they tell about them, getting a laugh because of them. But some, or many, of these relatives were not Christians; they never converted. They died in their sins. Thus the church would have to regard them as being damned in Hell. Yet I inexorably sense that these women (men too) secretly believe that their relatives died in grace, that somehow God went ahead and saved them. Perhaps they wouldn’t converse about them if they didn’t. It’s like this: They had a grandpa who never lived a Christian life—never—but it’s okay. God didn’t allow him to go to Hell. He will be judged, yes, but not damned. Why should they believe such a thing?

They do, however, or they behave as though they do. Are they secretly noticing an outrageousness in the damnation doctrine? Do they suspect (I more than suspect) that the traditional church is wrong?

by Dean | Apr 11, 2018 | General

English: Folio 18 recto, beginning of the Epistle to Thessalonians, decorated headpiece (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

So: the anti-Christian persecutors of Second Thessalonians 1 will receive “everlasting destruction.” The teaching has long existed that a more proper translation is “destruction of the age,” or maybe “age-during destruction.” That is, a destruction belonging to an age. The Koine Greek word for everlasting, aionious, does not mean everlasting. It refers to a period of time. “Everlasting punishment” in Matthew 25 is punishment of the age.

Where does this leave Hell?

by Dean | Apr 1, 2018 | General

-

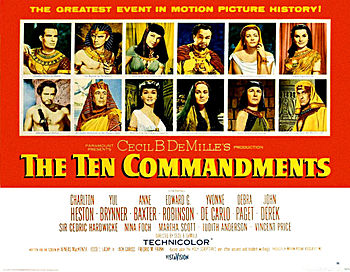

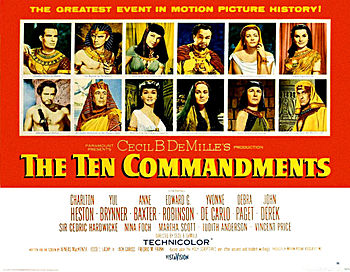

Movie poster of The Ten Commandments. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The acting in Cecil DeMille‘s The Ten Commandments is not always good, so it’s a wonder the thespians manage to exude as much true spirituality as they do. Not that it is never artificial—of course it is—but the artificiality of the entire picture fails to upend the spiritual feeling DeMille was after.

- Since the ancient Egyptians worshipped many gods, cats included, surely it is unsurprising to find an Egyptian woman, Anne Baxter‘s Nefretiri, worshipping a handsome non-god, Moses (Charleton Heston). Baxter is beautiful, her acting nicely precise in its dreaminess. Debra Paget and Yvonne De Carlo are beautiful too, but do not have much impact here.

- It was inspired of the screenwriters to have Joshua (John Derek) paint lamb’s blood on the doorposts and lintel of the house where Lilia (Paget) is being kept by middle-aged Dathan (that pig!) It means firstborn Lilia doesn’t have to die. Ah, Moses, however, tells the stricken Nefretiri—nothing really goes right for her—that he is unable to save the life of her small son, and yet this is not true. He simply needs to urge her to arrange the painting of lamb’s blood on her doorposts and lintel.

Cropped screenshot of Anne Baxter with Yul Brynner from the trailer for the film The Ten Commandments. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

by Dean | Mar 28, 2018 | General

Pickup on South Street (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The Sam Fuller film, Pickup on South Street (1953), is probably the only movie ever made in which a prostitute, or former prostitute, is accused of being a subversive Communist. But the woman in question, Candy (Jean Peters), simply doesn’t know the company she keeps, and is, it turns out, badly roughed up by a Communist. Skip McCoy (Richard Widmark), a cynical thief, gets rough with her too—welcome to New York City—but later the two become, er, committed lovers.

Fashioned under the studio system, Pickup is better directed, more polished, than Fuller’s White Dog, and just as absorbing. This despite a couple of defects in Fuller’s screenplay: e.g. Thelma Ritter‘s character never would have stayed alive as long as she does. I like most of the acting, except that Murvyn Vye, as a police captain, never changes his scowling expression.

by Dean | Mar 25, 2018 | General

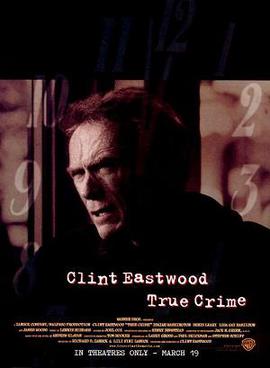

Film poster for True Crime – Copyright 1999 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Clint Eastwood miscast himself as a newspaper reporter in the 1999 True Crime, but a bigger problem is the weak plot. Based on an Andrew Klavan novel, the film’s serious subject is the death-row conviction of an innocent man (Isaiah Washington). Steve, the reporter, interviews people for his paper but he also likes to play Dick Tracy, and he doesn’t understand how a male witness, after a homicide, could have seen the innocent convict’s gun through a rack of potato chips. Nice try, but this won’t fly as a plot device.

On the positive side, the anguish of the convict and his family is handled movingly, and there is a powerful scene of marital breakup featuring Eastwood and an extraordinary Diane Venora. Both these scenes belong in a better movie—one, in fact, that doesn’t rely on constant profanity and obscenity to hold a viewer’s attention. (Thanks, Clint, for your use of James Woods in this regard.) True Crime is somewhat of an offense.

by Dean | Mar 19, 2018 | General

Poster for ”La Règle du jeu, directed by Jean Renoir (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

In the late 1930s, film artist Jean Renoir was not happy with French society, which he exposed in La Regle du jeu (1939)—The Rules of the Game—as unserious and self-seeking and infernally adulterous. Curiously, class distinctions take a step back (both Christine and her chambermaid cheat on their husbands), but the camaraderie we see is usually limited to one’s own class. And yet this camaraderie, such as that between Christine and Genevieve de Marras, quickly departs, and certainly without it, there is mayhem.

For all this, The Rules of the Game is a “pleasant” movie (Renoir’s word, translated); it is pronouncedly comical. It is a classic, made so partly by some excellent acting. Marcel Dalio, for example, looks right as the Marquis Robert, but is also unerring with the character’s casual decadence and tired vigor. Mila Parely, another example, cleverly plays Genevieve, the marquis’s mistress, displaying a range of emotion as admirable as her poise. But why was Rules Renoir’s last great film?

(In French with English subtitles)