by Dean | Nov 2, 2017 | General

Little Fugitive (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The Morris Engle-Ruth Orkin picture, Little Fugitive (1953), probably influenced European cinema of the late Fifties and early Sixties, but I could never claim it has much to say. What I do claim is that it is a dandy representation of boyhood in America, and is refreshingly honest about young-male emotions and concerns.

With his tough-as-nails little voice (necessarily dubbed), Richie Andrusco plays the “little fugitive,” he who, because of a prank, believes he has killed his 12-year-old brother; but has not. Afraid, the boy takes off and—what do young New Yawkers like to do? Go to Coney Island, which is what the little fugitive does. For the most part, as the lad amuses himself at C.I., he is emotionally unaffected by the “killing” of a brother whose relentless teasing the boy hates. . . Little Fugitive is an urban, primitive-looking independent film with nonprofessional actors. It was released at a time when American movies, though usually inartistic, were very gradually taking chances (as witness Beat the Devil, Night of the Hunter, The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T., The Girl Can’t Help It). We’re fortunate the Engel-Orkin movie, not so inartistic, was made.

by Dean | Nov 1, 2017 | General

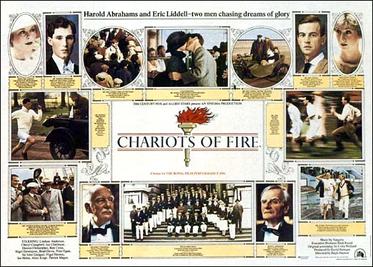

Chariots of Fire (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Early in the film Chariots of Fire (1981), a working class chap comments apropos of two Cambridge students that British young men fought a hellish war (World War I) so that “shits like [the two students] could get a decent education.” But the wealthy need not be ashamed—here, they’re clearly not a bad lot—and the fought-for Great Britain is loved by its citizens, young men and the rest.

Of course Great Britain is imperfect, as is the twentieth century. If it is not banal to say so, where perfection exists is in commitment to something worthwhile, and so Cambridge student Harold Abrahams (Ben Cross), a Jew, is committed to a Jewish victory in competitive running. This in the midst of British anti-Semitism. There is also commitment in Eric Liddell (Ian Charleson), a Scottish Christian and another runner, and this is good. A modern Britain, after all, seems to pose a desultory threat to religion: it balks at Liddell’s refusal to run a heat on Sunday. It is a favor done by a particular Cambridge student which enables the young man to participate (in the 1924 Olympics). In Chariots of Fire, many moments of light, in England, follow the terrible war years. Granted, there is nothing redemptive in all the Olympic running, but what about the religious lives of people—religious dedication?

by Dean | Oct 30, 2017 | General

I simply do not like the films of Nicolas Roeg.

Don’t Look Now (1973) is a fancy, fatuous occult-heavy—and thus supernatural—thriller. Hitchcock’s scary Frenzy, which came out close to the same time as Roeg’s movie, is offensively misogynistic, but at least it relates a sensible story. Don’t Look Now is an infernally messy puzzler.

Hilary Mason, as a psychic named Heather, is wonderful in the film, and so is Clelia Matania as her sister. They deserve a better movie—but then, so does almost everyone else in the film’s cast.

by Dean | Oct 29, 2017 | General

Roxanne (film) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

John Simon asserted that Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac is not a great play, merely a perfect one (which amounts, of course, to a great deal). The 1987 movie that Fred Schepisi and Steve Martin derived from Cyrano—entitled Roxanne—is neither great nor perfect, but it is mightily amusing and slightly literate. It has a pleasant cast too: a not-bad Daryl Hannah, a comfortable Shelley Duvall and Rick Rossovich.

Steve Martin, the film’s modern Cyrano, can go overboard as both actor and writer. Approvingly, Pauline Kael wrote that Martin “seems to crossbreed the skills of W.C. Fields and Buster Keaton . . . ” Well, he has some of Keaton in him, but certainly none of what Fields had. He isn’t down to earth. But he too is pleasant: in Roxanne, he is an actor of personality, of zany savoir-faire.

by Dean | Oct 26, 2017 | General

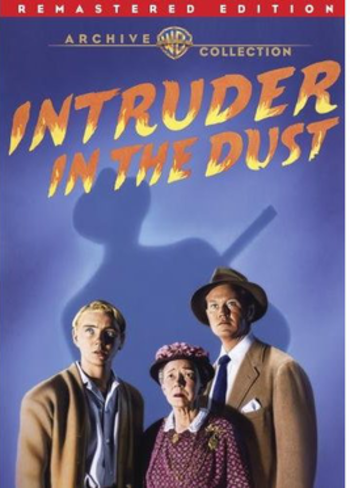

Intruder in the Dust (1949 film) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

A brave old lady (Elizabeth Patterson) initiates the digging up of a dead body after nightfall to see what kind of bullet was used to kill the person. The boys who assist her are brave too. What prompts this action—a plot device in Clarence Brown‘s Intruder in the Dust (1949)—is the swift arrest of a black man, Lucas Beauchamp (Juano Hernandez), for the murder of a white man.

The film, based on a William Faulkner novel, is set in the South and was shot in Faulkner’s home town of Oxford, Mississippi. A finely directed piece, it concerns the perennial struggle for the rule of law, for just procedures for every accused individual (a lesson needed in today’s America). Lucas has a friendly relationship with a white boy called Chick (Claude Jarman, Jr.) and, in fact, with money, for he is a well-off farmer in a slowly changing America. But the townspeople disdain his pride, and desire a lynching, and yet scriptwriter Ben Maddow does supply a few essentially good people. In the case of the murdered man’s father (a strong Porter Hall), this seems to be due to the gent’s having been seasoned by harsh life—the very thing Faulkner never ignored.