by Dean | Oct 6, 2016 | General

Edith Wharton’s “Atrophy” is a first-rate short story about . . . well, the atrophy, the wasting away of human relationships. It parallels the physical condition of the ailing illicit lover of Nora Frenway, married to a man with his own “weak health” as well as a “bad temper” and “unsatisfied vanity.” So, yes, there has been adultery: Nora tries to visit the ailing lover, who is unmarried, but is coolly prevented by the man’s sister. If an illegitimate affair is not insufficient in one way, it will be insufficient in another.

As good as “Atrophy” is, I’m glad Wharton didn’t write about adultery in the late story, “All Souls’.” This, as the narrator remarks, “isn’t exactly a ghost story,” although it is assuredly a mysterious one wherein the practice of the dark arts might be taking place. After breaking her foot, the recuperating Sara Clayburn believes her house is, except for herself, empty of people and completely, eerily silent, but her maid Agnes denies this. That a strange woman on All Soul’s eve might have something to do with this phenomenon is perhaps what keeps Sara from seeking the “natural explanation of the mystery” she hopes is there. We may hope it is too, but what if the dark arts are involved?

After reading these stories, and two others I perused some years ago, I have to wonder if it was possible for Wharton to pen a bad short story. She was a born fiction writer.

by Dean | Oct 4, 2016 | General

Cover of Xiu Xiu: The Sent Down Girl

The Chinese actress, Joan Chen, has a fine if very unhappy film in Xiu Xiu: The Sent Down Girl (1999), which Chen directed and co-wrote.

Clearly influenced by the artistic drive and anti-totalitarian pessimism of such directors as Zhang Yimou and Tian Zhuangzhuang, Chen’s story is that of a city girl’s emotional and spiritual decline after she is sent by the Mao government to work in the country as a horse-herder. This is during the 1970s, and the imposed duty is supposed to be temporary, but . . . Xiu Xiu comes to learn of the Red system’s cruel neglect and dehumanization of its citizens.

Lu Lu enacts the title role with spunk and sparkle and convincing pathos. Lopsang provides manliness and charm as the Tibetan horse-herder in charge of young Xiu Xiu—he who never has sex with the girl (unlike some vile Communist officials) because he has no male organ. But what stands out more than the performances is the way this compelling film was made. The editing and Chen’s directing are mercurial but adept, as is evident from the footage of the plains. Adroitly captured are the boredom and solitude in this region of wind, grass, horses and expansive skies. A surfeit of closeups appears (a common gripe of mine) but nice things are done with proliferating medium and long shots too. As for Lu Yue’s cinematography, it is decidedly suitable for the bald realism in the film; it is dim only when it ought to be and never overlighted. It avoids the postcard beauty that critics are always objecting to, and yet its colors aren’t ugly either. It is a memorable film. Good choices, Miss Chen. Good work.

by Dean | Sep 29, 2016 | General

American Beauty (film) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

American Beauty (1999) is about a discontent suburbanite whose go-getter wife and truculent daughter disdain him, and who falls in love with his daughter’s beautiful best friend. It involves some other folks too, among them a harsh Marine officer who is a repressed homosexual. Whoa! Bad idea, you say? Yes, it is; as hoary as it is cheap. The Marine’s homophobia is frowned on, his “reactionary” love of discipline scorned. He must be made to pay. Curiously, however, his dope-pushing, dope-smoking son receives the filmmakers’ sympathy (though, in fairness, his father receives some too) and is never made to pay.

Homosexuality, though, is not a major subject here. Heterosexuality is. The heterosexual lives, that is, of the characters played by Kevin Spacey (the discontent suburbanite), Annette Bening, Thora Birch, et al. While watching the film I thought another subject it was about was the folly of the American dream, but not exactly. It makes the point that this dream is not such a folly after all, that it is perhaps . . . one of the beauties of America? In my view the beauty of the American dream goes only so far, but in any event, whatever is being said, the movie’s conclusion doesn’t cut it: it’s both rosy and stupidly implausible. It doesn’t convince us of the goodness of the American dream. It merely confirms that the film has gone awry.

Though deeply blemished, American Beauty does have its assets. What with Sam Mendes‘s bright direction, Conrad Hall’s flawless cinematography, and Thomas Newton’s eccentric yet restrained music, it tries to be art. Many images are superbly sensuous, and not just the sexy ones. The technicians here knew what they were doing; the screenwriter, Alan Ball, didn’t. His script’s profundity is nil.

If you want an inoffensive, non-tendentious opus about an unhappy married man who falls for a teenage girl, read John Cheever’s story, “The Country Husband.” It is five times as appealing as American Beauty, for all its dandy visuals.

by Dean | Sep 27, 2016 | General

The Bridge on the River Kwai (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), by David Lean, is a film of elevations. People move around on top of mountains, banks, bridges; and there are shots of the sky above treetops. Natural (and manmade) grandeur is frequently close to where men are working and warring and suffering.

Lean has a perfect sense of this grandeur, while—-regrettably—his film is weak in characterization. Colonel Nicholson (Alec Guinness) and the soldier Shears (William Holden) seem like prototypes of something but not much more, and so they’re obscure. However, it is fine for the picture to ask what is and what is not insanity in war, and to point out the insanity of helping the enemy: the Japanese army in WWII.

A British-American effort filmed in Ceylon, Bridge is Lean’s first epic. It’s not necessarily one of his best movies, but it shares with his other works the benefit of unmistakable art.

by Dean | Sep 25, 2016 | General

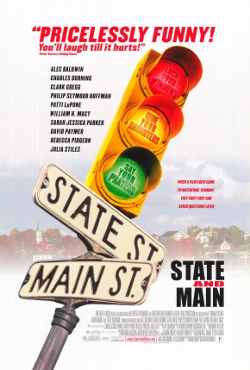

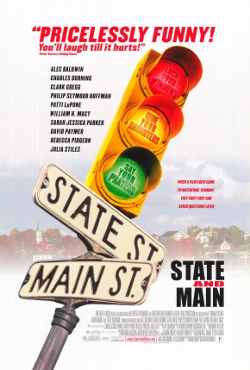

State and Main (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

David Mamet‘s film, State and Main (2000), concerns contretemps and obstacles between a moviemaking team and the citizens of a town called Waterford, Vermont, where the team are fashioning a film. The characters captivate: William H. Macy‘s agitated director, Alec Baldwin‘s hugely popular actor and nymphet-loving pervert, Rebecca Pidgeon’s bright, affable bookstore owner, Philip Seymour Hoffman’s diffident scenarist, and many others.

Like the witty dialogue, the plot is fun except that a glaring defect springs up when Clark Gregg‘s pushy prosecutor tries to build a statutory-rape case against Baldwin when he certifiably has no case at all. Gregg—his character—wouldn’t be that stupid. But something else bothers me more: Mamet, in truth, has nothing new to tell us about corruption or Hollywood folly, and that is entirely what his film is about. All State and Main can do is dispense airy cynicism—well, that in addition to showing us that somewhere deep inside Mamet he is a glorifier of the past. Not merely deep inside, of course, he is a conservative.

Mamet’s 1999 The Winslow Boy worked (as did his Phil Spector). The present film almost works, but not quite. Even so, it’s one of the most enjoyable failures I’ve seen, and if you can put up with airy cynicism you might enjoy it too.