by Dean | Oct 30, 2017 | General

I simply do not like the films of Nicolas Roeg.

Don’t Look Now (1973) is a fancy, fatuous occult-heavy—and thus supernatural—thriller. Hitchcock’s scary Frenzy, which came out close to the same time as Roeg’s movie, is offensively misogynistic, but at least it relates a sensible story. Don’t Look Now is an infernally messy puzzler.

Hilary Mason, as a psychic named Heather, is wonderful in the film, and so is Clelia Matania as her sister. They deserve a better movie—but then, so does almost everyone else in the film’s cast.

by Dean | Oct 29, 2017 | General

Roxanne (film) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

John Simon asserted that Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac is not a great play, merely a perfect one (which amounts, of course, to a great deal). The 1987 movie that Fred Schepisi and Steve Martin derived from Cyrano—entitled Roxanne—is neither great nor perfect, but it is mightily amusing and slightly literate. It has a pleasant cast too: a not-bad Daryl Hannah, a comfortable Shelley Duvall and Rick Rossovich.

Steve Martin, the film’s modern Cyrano, can go overboard as both actor and writer. Approvingly, Pauline Kael wrote that Martin “seems to crossbreed the skills of W.C. Fields and Buster Keaton . . . ” Well, he has some of Keaton in him, but certainly none of what Fields had. He isn’t down to earth. But he too is pleasant: in Roxanne, he is an actor of personality, of zany savoir-faire.

by Dean | Oct 26, 2017 | General

Intruder in the Dust (1949 film) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

A brave old lady (Elizabeth Patterson) initiates the digging up of a dead body after nightfall to see what kind of bullet was used to kill the person. The boys who assist her are brave too. What prompts this action—a plot device in Clarence Brown‘s Intruder in the Dust (1949)—is the swift arrest of a black man, Lucas Beauchamp (Juano Hernandez), for the murder of a white man.

The film, based on a William Faulkner novel, is set in the South and was shot in Faulkner’s home town of Oxford, Mississippi. A finely directed piece, it concerns the perennial struggle for the rule of law, for just procedures for every accused individual (a lesson needed in today’s America). Lucas has a friendly relationship with a white boy called Chick (Claude Jarman, Jr.) and, in fact, with money, for he is a well-off farmer in a slowly changing America. But the townspeople disdain his pride, and desire a lynching, and yet scriptwriter Ben Maddow does supply a few essentially good people. In the case of the murdered man’s father (a strong Porter Hall), this seems to be due to the gent’s having been seasoned by harsh life—the very thing Faulkner never ignored.

by Dean | Oct 24, 2017 | General

Cover of All the King’s Men

The 1949 All the King’s Men is crisp and fluid as it tells of a flatly indecent governor (Broderick Crawford‘s Willie Stark). It has a better, if blemished, script than Citizen Kane, another film about a powerful man, because it’s adapted from Robert Penn Warren’s novel. There is recklessness and perfidiousness that remind us of Jack Kennedy and Ted Kennedy (Chappaquiddick), and demagoguery that reminds us of many of the most offputting politicians.

I would declaim to my dying day that the remake of King’s Men starring Sean Penn is a stupid movie, but that is not my opinion of the ’49 original. Moreover, most of the chief cast members in the ’49 film actually outact the later chief cast members, with a Crawford who is not mannered at all, purveying a Willie Stark who is not a caricature. For all this, why the former newspaper reporter (John Ireland) stays with the naughty Stark to the end is anybody’s guess.

by Dean | Oct 19, 2017 | General

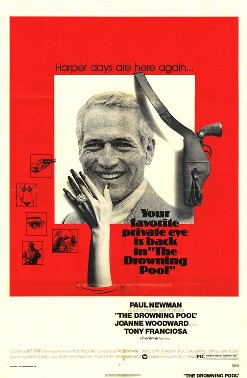

The Drowning Pool (film) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

With the car washing scene in Cool Hand Luke, director Stuart Rosenberg was a bit of a sexist, but not in The Drowning Pool (1975), which hardly means it is a good film. The fault is not Rosenberg’s, though, but that of the writers, including, I assume, Ross MacDonald, whose novel is the source for this.

A detective movie starring Paul Newman as Lew Harper, The Drowning Pool serves up two villains, one of whom is an inadequate actress and hard to swallow as a villain, the other of whom is an appalling oil man. (Ho hum.) The oil man is so stupid he makes it possible for someone to rip off an incriminating account book of his (he’ll kill to get it back). It’s pretty underwhelming material, made in such a way as to make it seem more than that. But underwhelming is all it is. From car wash to drowning pool—not a step up.

by Dean | Oct 18, 2017 | General

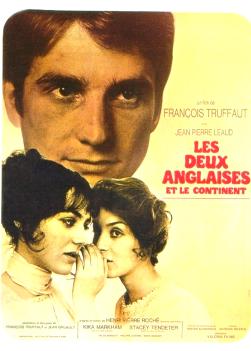

Two English Girls (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Francois Truffaut‘s fine 1971 film, Two English Girls, seems intent to tell us that young men and women cannot be close friends, that personal sacrifice cannot withstand non-conjugal physical desire. Based on a novel by Henri Pierre Roche, just as Jules and Jim is, it revolves around two women (sisters) and one man, unlike the two men and one woman of Jules.

Stylistically Truffaut is probably a bit over-imaginative, but he also proves what an excellent eye he has. He gives us a likable overhead shot of Claude (the man) and Muriel (one of the women) atop a high hill with the tiny figure of Muriel’s sister Anne—before she disappears in an iris-out!—at the bottom of the hill. He provides a smart scene in which Muriel, a thirty-year-old virgin—circa 1900—has her full-cover 19th century apparel slowly removed from her by the aforementioned Claude, whom she loves. Standing at last with her attractive mammaries exposed, she virtually symbolizes all humanity poised before an era of gradual sexual freedom (and all its unfortunate consequences).

In an earlier review of Two English Girls, I said it is inferior to Jules and Jim. Not so. Girls is not tedious. It is sad, which indeed is connected to its real feeling for suffering (mostly Muriel’s). It remains what I called it earlier: guileless and humane. If I live to be very old, chances are I’ll read the novel.

(In French with English subtitles)