by Dean | Sep 18, 2016 | General

Cover of Black Rain

Japan’s Black Rain (1988) is about disease. And Hiroshima. The disease is radiation sickness, ergo the cause is the bomb.

The film begins on August 6, 1945, when Hiroshima got it in the neck, and a more horrid city catastrophe you will not find in a movie, albeit to his credit director Shohei Imamuri does not rub our noses in it. Several screen minutes later, it is 1950 in a prosaic Japanese village; inhabitants live their quiet lives there. But, tragically, many of these inhabitants were in or near Hiroshima five years ago, and some are getting ill. The film’s narrative, adapted from a novel by Masuji Ibuse, is pivoted on an aunt’s and uncle’s efforts to marry off their 25-year-old niece Yasuko (Yoshiko Tanaka), about whom there are village rumors that she too is ill. The aunt and uncle have radiation sickness, but what of Yasuko, who was never actually in Hiroshima? Are the aunt and uncle lying to themselves in thinking their niece may be physically fit for marriage?

For two full hours Black Rain gives us much to see and a goodly amount to think about. It is reticently angry, hating the weapons of warfare (with no vicious Japanese soldiers appearing); it is bleak and compassionate. Some of the finest scenes include the one where, outside Hiroshima in a boat on a river, Yasuko’s young face gets spattered by the titular “rain” that is the result of the awesome explosion. And the one where Yasuko’s aunt, so sick she is hallucinating, imagines she sees four men whom radiation sickness has already killed brazenly opening the windows of her home. Too, a semi-charm emerges in the scene where a brash young man kisses and tells Yasuko that he loves her (before losing his balance on a pile of rocks he is standing on), but no charm at all can be found—of course—when, some time later, Yasuko examines her face in a mirror, looking for evidence of the malady. And does she think she sees it?

Imamura has done superlative work here. Since I haven’t read Ibuse’s novel, I can’t say whether the film does justice to it but it immediately makes you suspect that it has. One takes pleasure in being unable to detect hardly any artistic flaws at all, certainly no serious ones. It reminds us of the greatness of the most skillful Japanese films.

by Dean | Sep 15, 2016 | General

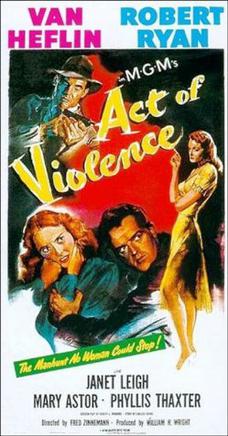

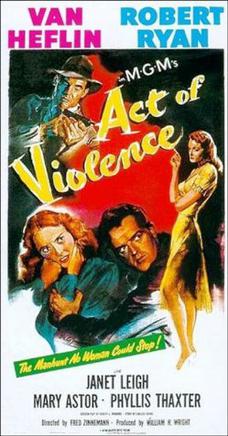

Act of Violence (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

An early Fred Zinnemann flick, Act of Violence (1948), is at least plausible: A vengeful lame man (Robert Ryan) with a nice girlfriend is hunting a married suburbanite (Van Heflin) who wreaked terrible damage by turning into an informer for the Nazis. Both men were in a German concentration camp; now Ryan wants to kill Heflin.

To me, this mere plausibility pleases less than the movie’s momentum—and Zinnemann’s control. How well he works with his actors! Ryan is perfectly somber without being a goon. Heflin is every inch an ordinary suburbanite reduced to a pursued wreck. Vincent Minnelli couldn’t get much energy from Mary Astor in Meet Me in St. Louis, but Zinneman does in this film.

Act of Violence ends with an unfortunate stinting on sympathy for the Janet Leigh character (who is married to the ex-informer), but at any rate Leigh, too, gives a committed, vigorous performance. And she looks like a million bucks.

by Dean | Sep 14, 2016 | General

![Cover of "Minority Report [Blu-ray]" Cover of "Minority Report [Blu-ray]"](//ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51uRGD7j7sL._SL350_.jpg)

Cover of Minority Report [Blu-ray]

Washington D.C. in 2054 has apparently solved the social problem of murder through the use of a trio of humans known as “Pre-Cogs,” who mystically predict when homicidal deeds will occur. Tom Cruise‘s John Anderton is at the helm of the Justice Department’s precrime unit which employs the Pre-Cogs. The plot crisis breaks out when it is predicted that Anderton himself will soon murder a man he does not even know; did the Pre-Cogs make a mistake? Anderton believes he is being set up, but by whom? And how?

Anything but dull, this Steven Spielberg science-fiction picture is nevertheless a flop. Anthony Lane, in The New Yorker, declares that “Spielberg the liberal is asking what the dangers might be when law and order submit to logic and nothing else.” Okay. But the liberal Minority Report is not exactly early John Dos Passos. In reality, law and order are not always submitting to logic in the film: it is asseverated that the Pre-Cogs occasionally disagree with each other about a future homicide. Yet an arrest is made anyway. The film is not so much about dystopia logic as dystopia injustice. Unfortunately, the Scott Frank-Jon Cohen screenplay (based on a Philip K. Dick story) is maddeningly absurd, especially with all that Pre-Cog fairy-tale stuff. Things are hardly improved by the aging character enacted by Max von Sydow. I like von Sydow, but not the part Spielberg gave him to play.

Tom Cruise’s part is fine, vital, but Cruise performs uninterestingly. Janusz Kaminsky provided Spielberg with the locker-room hazy, supremely dank cinematography the director wanted. But why did he want it? Alex McDowell’s futuristic production design is easer to take, for even the cinematography can’t undermine it.

by Dean | Sep 12, 2016 | General

France with its Catholicism exists, of course, in Madame Bovary, but it is somewhat more pronounced in Francois Mauriac‘s short novel, Therese Desqueyroux (1927). After all, Mauriac was a Christian—or on the verge of becoming one when he wrote Therese—and his titular heroine commits a grave sin by trying to poison to death her husband Bernard. Peculiarly Bernard, with Therese’s father, works out an exoneration for Therese, but he also forces her to live in near-confinement in his house—a kind of penance. This goes on for a limited time, however.

I have not read in full Mauriac’s other three fictions about Therese, but apparently the errant woman finds God in the one called “The End of the Night,” which I cannot get through. It is Therese Desqueyroux that I find riveting as well as superb, albeit therein there is no salvation. Yielded by the story is the message that a marriage not founded on love can lead to the worst perversion, and such themes as the spiritual worth of a friendship (that of Therese and Anne de la Trave) but also its transience.

by Dean | Sep 11, 2016 | General

Cover of Madame Bovary

Isabelle Huppert is extraordinary as Emma Bovary in Claude Chabrol‘s Madame Bovary, a long 1991 effort. The formal achievement of Flaubert’s classic novel means that MB cannot really be filmed, but, besides the acting, what shines here is the directorial talent. Chabrol is after authenticity—in character, in locations, in boredom, in anguish—and gets it. He emphasizes only that which should be emphasized, and with a style never arty but always flavorous and even brave. Check out the dancing at the ball, the doctor’s “bleeding” of a patient, the scenes of an Emma buried under debt. No, we do not see Flaubert, but Chabrol and Huppert; and it’s fascinating.

Huppert has truly gone from strength to strength. In the 1970s film The Lacemaker, she was quietly appealing; in Madame Bovary she is commandingly nuanced and gripping.

(In French with English subtitles)

by Dean | Sep 8, 2016 | General

![Cover of "The Gunfighter [DVD]" Cover of "The Gunfighter [DVD]"](//ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51%2BvWhQn1KL._SL350_.jpg)

Cover of The Gunfighter [DVD]

Gregory Peck plays a no-longer-mean shooting ace pursued by the brothers of a man he killed in self-defense. Henry King directed the film tidily and knowingly, and had a good editor in Barbara McLean. Peck never stumbles as a troubled man, though Millard Mitchell is too stiff as a tough marshal. Karl Malden proves his reliability in an early role.

This is King’s baby, but even more it is the baby of one William Bowers, who co-invented the story and co-authored the script.

![Cover of "Minority Report [Blu-ray]" Cover of "Minority Report [Blu-ray]"](http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51uRGD7j7sL._SL350_.jpg)

![Cover of "The Gunfighter [DVD]" Cover of "The Gunfighter [DVD]"](http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51%2BvWhQn1KL._SL350_.jpg)