by Dean | Mar 23, 2014 | General, Movies

Cover of Top Hat

I’m no judge of choreography, but that involving Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in 1935’s Top Hat strikes me as palatable, not silly or clumsy or pretentious. More appealing are the Irving Berlin songs, all of which have decent melodies, one of which (“Cheek to Cheek”) has an outstanding one.

Directed by Mark Sandrich, Top Hat is a delicious musical comedy, as are other Astaire-and-Rogers musical comedies, and one which takes the comedy in its genre seriously, however trivial these nonstop jokes may be. No, they’re not Oscar Wilde but at least they’re funny. As for the actors, they form a rather remarkable comic ensemble, even the two dancing stars: beau-less Ginger, blurting out, “I HATE men!” holds her own. Always, of course, she held her own as a dancer, though with fewer sparks than Astaire, who has among other things the “damn-your-eyes violence of rhythm” (Otis Ferguson).

Top Hat was nominated for an Oscar for best interior decoration, but I’d rather see the damning-your-eyes. The interior decoration is dated now; Astaire’s dancing isn’t.

by Dean | Mar 14, 2014 | Movies

Night Must Fall (1937 film) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

In 1937, what I assume to be a suspenseful play by Emlyn Williams became a suspenseful motion picture. I mean Night Must Fall, superbly directed for the screen by Richard Thorpe and featuring crisp and clever acting from Robert Montgomery, Dame May Whitty and Rosalind Russell.

In it, an extroverted page boy (Montgomery) wins the heart of, and is hired to work for, a nasty old woman and pseudo-invalid (Dame Whitty) who is daily disappointed by the ministrations of her live-in niece (Russell). The page boy is sexually attracted to the niece and she to him, except that a news report of a missing girl in this English vicinity induces the niece to suspect that the page boy is in reality a Jack the Ripper. Of course this leaves her cold but also fascinates her. In fact both characters are eccentrics, one of them creepy and the other, the niece, repressed. The latter makes the claim, in effect, that the page boy has taken away her reason.

Night Must Fall is about a world of ordinary petty spite (the old woman’s) and ordinary vulnerabilities when it confronts a devilish phenomenon. It has to do with when there arises a perversion greater than your own—greater, that is, than the old woman’s, but also greater than the niece’s temporary perversion when she loses her “reason.” Moreover, it is about the mystery of human motives. It is a thriller about terror, made by Thorpe with an eye for cinematics.

by Dean | Mar 12, 2014 | Movies

The excellent Chilean film Gloria (2014), by Sebastian Lelio, concerns a woman in her (late?) 50s who desires a man, acquires one, and then suffers because of his curious behavior. Intercourse takes place right away, followed by pleasurable hanging-out, followed by the overcautiousness and divided attention of Rodolfo, the near-elderly “boyfriend.” For Gloria, the heroine, a mini-disintegration goes on, and her conduct is sometimes repellent. When a reasonably strong person is agonized is a concern here, and the simple uplift at the film’s end amounts to very little. But it is there.

The excellent Chilean film Gloria (2014), by Sebastian Lelio, concerns a woman in her (late?) 50s who desires a man, acquires one, and then suffers because of his curious behavior. Intercourse takes place right away, followed by pleasurable hanging-out, followed by the overcautiousness and divided attention of Rodolfo, the near-elderly “boyfriend.” For Gloria, the heroine, a mini-disintegration goes on, and her conduct is sometimes repellent. When a reasonably strong person is agonized is a concern here, and the simple uplift at the film’s end amounts to very little. But it is there.

The picture is like an extended artistic short story, with enticing cinematics (everything from the cinematography to the white peacock). The middle-aged nudity is ugly, though; Gloria does the full frontal. In truth, this is part of the evidence that actress Paula Garcia (Gloria) goes the whole nine yards for her stellar role, but I wish Lelio had not required her to go that far.

She does an extraordinary job of acting, however—now amiable, now solemnly bitter—and Sergio Hernandez is unbeatable as sheepish, unthinking Rodolfo.

(In Spanish with English subtitles)

by Dean | Mar 9, 2014 | Movies

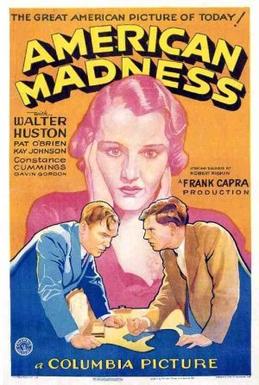

American Madness (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Tom Dickson (Walter Huston) is a bank president who nobly considers depositors his friends and is unconcerned about profit. Though serious about banking, he is the most humane of businessmen—and the hero of Frank Capra’s Depression-inspired film, American Madness (1932).

The madness of the title is a foolish run on Dickson’s bank by depositors terrified by a big loss of money owing to an embezzler named Cluett (Gavin Gordon). Dilemmas befall the bank president: he begins to fear losing both the bank and, as it happens, his marriage.

Hollow optimism about human nature—Capra’s familiar trait—finally springs up in the film, and there is an inconsistent tone (which is why Madness is a semi-comedy). Yet Robert Riskin’s script is a pretty effective character study, not incisive but humanly appealing. Too, it’s beguilingly smart, filmed by a dedicated and likable craftsman who worked well with his actors.

by Dean | Mar 6, 2014 | General, Movies

Français : Logo de la minisérie THE KENNEDYS. Français : Logo de la minisérie THE KENNEDYS. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

To me, one of the best “movies,” if you will, of 2011 aired on TV and was eight hours long (eight episodes long). It was The Kennedys, a docudrama not entirely free of blandness but also workmanlike and discerning.

Greg Kinnear is good as JFK, Tom Wilkinson terrific as Joe Kennedy Sr. in all his corruption. As the elegant Jackie, Katie Holmes looks the part but histrionically lacks conviction. The show’s focus is always on the mark, with the Cuban missile crisis covered vividly and painstakingly. An air of sympathy and compassion never goes away even as hagiography never intrudes.

The Kennedys is available on DVD.

by Dean | Mar 4, 2014 | General, Movies

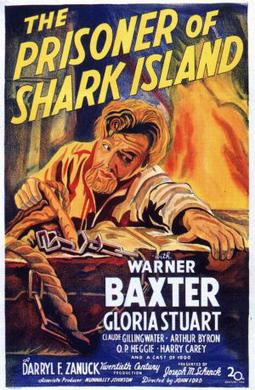

The Prisoner of Shark Island (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The John Ford film, The Prisoner of Shark Island (1936), is about Dr. Samuel Mudd, who treated the broken leg of John Wilkes Booth shortly after Booth murdered Lincoln and was consequently arrested for conspiracy to assassinate (!) and sent to serve a life sentence in the Dry Tortugas.

When a decent man is victimized by the authorities—this is the message conveyed. As the terrible incidents roll, also conveyed are all kinds of values (and virtues): courage, persistence, belief in God, marital love and, despite the country’s injustice to Dr. Mudd, patriotism. Plus there is military pride, as demonstrated by Mudd’s crotchety father-in-law, an elderly Southern colonel (Claude Gillingwater). Today both he and Mudd would be seen as politically incorrect (yawn): the doctor, you see, is a decent, estimable SLAVER.

Prisoner is still riveting, and I agree with film critic Otis Ferguson about the strength and worth of the prison escape sequence. Nunnally Johnson’s script provides more depth than we generally get from Ford’s Westerns, even if the old American movies never enabled us to feel the ineradicable wound of life. Their unpleasantness was limited.