by Dean | Nov 17, 2016 | General

In Pupi Avati‘s exquisite Italian picture, The Best Man (1997), the narrative unfolds on the last day of 1899 when a young woman called Francesca (Ines Sastre) is expected to marry by parental arrangement an unappealing man. By no means does she love him, but to cancel the wedding would bring scandal and financial disaster to the family, and so Francesca goes through with it. Except that she falls in love at first sight with Angelo (Diego Abatantuono), one of the groom’s best men, and in her heart, she avers, he is the one she marries. Separated for years from a paramour of his own, heavy-hearted, self-doubting Angelo finds Francesca a real temptation and in truth cannot really condone the marriage, but he doesn’t condemn it either. The groom, after all, is his friend, albeit that friendship is obliterated once the groom learns of his new wife’s affection for Angelo. At length the wedding is seen to have been a mockery, but the fin de siècle arrives without Francesca being in the arms of “the best man” she assuredly loves. I will not reveal, however, the movie’s ending.

The fin de siècle—i.e., the end of the century—is important here. The characters gleefully look forward to the 1900s. Because she rebels against her arranged marriage, against the tradition of marrying not out of love but out of mere duty or habit, Francesca unwittingly behaves like a bona fide child of the new century. She represents a coming change of values. Ironically, the only person in the film who believes in marital Love is an ostensible lunatic, one of Francesca’s aunts. Curiously, Francesca seems to absorb this “lunacy,” to become crazy herself, and yet in fact she is eminently sane. Celibate now that her husband has apparently had the marriage annulled, she receives refuge in a country church and teaches Catholic schoolchildren (the clergy are good to her; there is no anticlericalism in this film). No doubt loneliness emerges in this kind of life, but so does sanity. More or less there is health here, and there are lunacies the West of the twentieth century will sweep away. (But the characters are foolishly optimistic. One man, after all, states it will be a century without war.)

The Best Man boasts a sensitive and sophisticated script, and its cast is very winning.

by Dean | Nov 15, 2016 | General

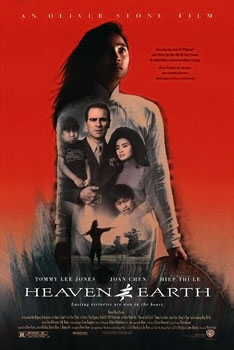

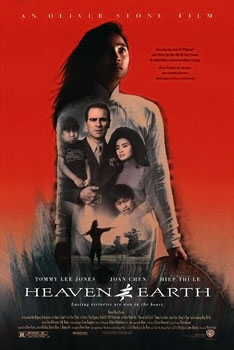

Heaven & Earth (1993 film) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

An unacceptable artist, not least because he is intellectually shallow, Oliver Stone has what is at bottom a Buddhist movie in the 1993 Heaven and Earth. Stone is fond of Buddhist thought here, but also he can be hard on the people of Buddhist Vietnam. Both the South Vietnamese and the Vietcong during the Indochinese war are barbarous; they rape and torture the film’s chief figure, Le Ly. Vietnamese civilians hardly prove angelic either. Stone is equally hard of course on Americans because of our intervention in that Far East conflict of the Sixties and early Seventies and our vulgar materialism.

Based on Le Ly Hayslip’s memoir, When Heaven and Earth Changed Places, about her life in Vietnam and then in the United States, the film follows the story of a Buddhist peasant girl, Le Ly, who marries an American serviceman. Their marriage is an unhappy one, with, uniquely, the Marines partly to blame because of how they tampered with the serviceman’s mind in Vietnam. Hiep Thi Le plays Le Ly superbly, with vulnerability, anger and youthful charm. Tommy Lee Jones is true and resounding as her husband. Stylistically, though, the film is irritatingly fancy and melodramatic. Stone does better with actors than with cinematic technique. There are some scenes that work very well, even so, such as the one where a military helicopter lands in, and causes a terrific spray of water over, a rice paddy where Le Ly is working. Or the one in which Jones, not yet married to Le Ly, chases the man-resisting girl down a crowded Vietnam street in a rickshaw. . . Heaven and Earth is mediocre, but if you can tolerate the occasional Buddhist philosophy, you might find worth your time its several real assets.

by Dean | Nov 13, 2016 | General

1970s society, in Christine (2016), has its mass media technology everywhere as well as its small and trivial consolations and “solutions”, e.g. Transactional Analysis, for life’s burdens. None of it does 29-year-old Christine Chubbuck any ultimate good. She is played, magnificently, by Rebecca Hall, but it is now widely known that Chubbuck was an actual person: a Sarasota TV reporter who, in 1974, shot herself on a live broadcast.

As played by Hall, Chubbuck is pretty and intelligent but neurotic, with an incessantly conflicted mind. Living with a socializing mother (J. Smith-Cameron), she herself is socially hindered. At the workplace she receives one blow after another, usually self-created, leaving her career un-advanced. Her hot-tempered boss (Tracy Letts), fighting for newscast ratings, is getting fed up with her.

Christine is one of the best movies about a life in decline I have seen, and—as Peter Rainer indicated—director Antonio Campos and scenarist Craig Shilowich wisely decline to turn Chubbuck into a martyr. What’s more, they demonstrate that a life ending in suicide is a life. A person is living it, is active and thinking and talking. All of this manages to be quite fresh. Characterization is handled knowingly and perceptively. The film is conventionally, flawlessly directed and (by Joe Anderson) photographed. I had to see it in an arthouse theatre—in Tulsa, at the Circle Cinema—and although it belongs there, it should also be at the multiplex.

by Dean | Nov 10, 2016 | General

Cover of Madigan

A police tale meant for adults, Don Siegel‘s Madigan (1968) is sort of a superfluous film without being a bad one.

It makes clear what we already know: Cops are only human, notwithstanding Detective Don Madigan (Richard Widmark) is essentially a mensch. Like other cops. Yes, he mistakenly lets a thoroughgoing bad guy (poorly played by Steve Ihnat) get away, but he proves competent enough for the center of the film: retrieving the creep.

Madigan is married to a selfish wife (Inger Stevens), but when the film focuses on the pair, what’s missing is a point of view. In fact, there is somewhat more of a character study of Henry Fonda‘s police commissioner than there is of Madigan. Too bad. But Widmark, Fonda, Harry Guardino and others are absolutely fine, whereas the acting of Stevens, the American Catherine Deneuve, is no better than that of Deneuve.

Another thing: It’s 1968, and New York City is starting to become really heinous.

by Dean | Nov 9, 2016 | General

This week’s Jane the Virgin had a nice flow to it and sensibly dealt with the difficulty of financially getting by. It was also briefly moving in its treatment of sad Luisa (a sapid acting job by Yara Martinez).

But probably nothing on TV this week will be as gripping as last night’s broadcast of the Presidential and Congressional elections. Spittin’ mad, foul-mouthed celebrities like Madonna and Rachel Bloom deserve what they got, but, well, the Republican voters who preferred Trump over Ted Cruz, Jeb Bush, et al. did not.