by Dean | Jan 12, 2017 | General

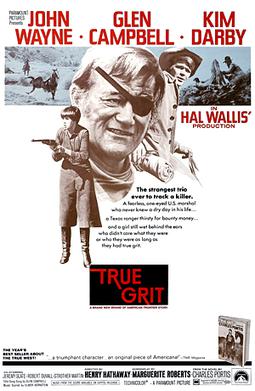

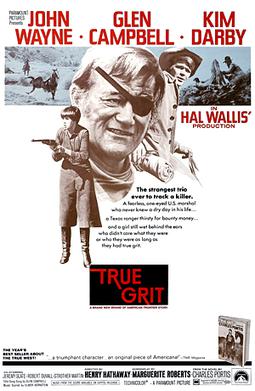

True Grit (1969 film) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

In 1969, the year of True Grit‘s release, critic Stanley Kauffmann found the movie offputtingly conservative. Mattie, the Kim Darby character, keeps mentioning that her family owns property, you see.

Whatever. It isn’t offputting to me. I enjoyed it for showing us the sweaty, economical drama that every intelligent Western is. It’s an acceptable adaptation of Charles Portis’s novel, neatly directed by Henry Hathaway. And, unlike Kauffman, I thought Darby filled the bill in her role.

by Dean | Jan 10, 2017 | General

Cover of Smile

The 1975 film, Smile, directed by Michael Ritchie and written by Jerry Belsen, is a morally searching comedy about a California teenage beauty pageant drenched in insincerity. Contest officials include extroverted Brenda (Barbara Feldon) and mobile-home salesman Big Bob Freelander (Bruce Dern), both of whom are generally amiable but also inclined, without knowing it, to morally settle: settle for something less than what character demands.

Brenda, for example, is wholly devoted to the pageant but frigidly keeps her sad-sack husband, Andy (Nicolas Pryor), at bay. Now Andy drinks. But such facts must never be revealed in the sphere of pretense the California town has constructed. Men here are frequently lecherous, ogling the young contestants who are innocent in several ways but can demonstrate selfish ambition as well. Smile is satire, often Swiftian but also humane; and it resembles traditional satire (the best kind) in that it purveys a standard of goodness in the course of its action. This standard is the behavior of Robin (Joan Prather), a humble, unhypocritical girl who loves, and is loved by, her widowed mother.

However, the film is not satire only. It is occasionally non-comedic: not meant to be funny. And its people often cease to be objects of jabs and ridicule, since, for one thing, they will do something admirable.

Certifiably Smile is flawed but, too, it is smart and interesting. It has splendid wit. It was written originally for the screen and it boasts a talented cast as long as some of the supporting players are excepted. But Dern, Annette O’Toole and others are savvy comic worthies. Further, a young Melanie Griffith (0ne of those mediocre supporting players) appears topless, but it isn’t gratuitous.

by Dean | Jan 9, 2017 | General

In The Diary of a Country Priest, the 1936 Georges Bernanos novel, the essentially unreligious (who may be laymen) sin and the young priest suffers. Cancer becomes his principal burden, and, although the priest finally dies, he is the one who comes out on top, as, to Bernanos, he must.

The thin plot has a local count conducting an affair with his daughter’s governess, and because the daughter, Chantal, resentfully knows about this, the count wishes to send her away. Meanwhile, the count’s wife is perpetually depressed over the death of her young son, and although she is less of a worry to the priest than Chantal is, it is the countess whose unexpected Christian conversion he engineers. He receives flak for it, though, after his methods are questioned. . . There is imperfection in this plot, but the characterization is strong—and the insights memorable.

Again, the unreligious sinners are here, but the sense is created that God is unwilling to reject or abandon them. A cosmic pendulum keeps swinging towards light before it swings back to darkness, and all souls are affected. Or at the very least we question whether all souls are affected. For instance, a soldier who respects Christianity nevertheless opines to the priest, “If God isn’t going to save soldiers, all soldiers, just because they’re soldiers, what’s the good of trying?” He is broaching the subject of how far the mercy of God goes. Consider, too, the priest’s following statement not about salvation but about human nature, sinful as this nature is: “the lowest of human beings, even though he no longer thinks he can love, still has in him the power of loving.” Bernanos’s novel offers Christian humanism at its best, perhaps at its most orthodox. As for our self-dissatisfied priest, he is not let down in any way, since near the end of the book he writes in his diary, “The strange mistrust I had of myself, of my own being, has flown, I believe for ever. That conflict is done.” That conflict is done before the priest dies in grace. It is a faithful Catholic, Bernanos, who provides this clear uplift.

Cover of The Diary of a Country Priest

by Dean | Jan 9, 2017 | General

“Diary of a Country Priest” (the novel)

by Dean | Dec 22, 2016 | General

Cover of Little Women (Collector’s Series)

Sets, costumes and cinematography are all worthy of the likable job Gillian Armstrong did on the ’94 version of Little Women, a U.S. production with Susan Sarandon and Winona Ryder. The film is a sweet, vigorous semi-fairy tale divorced neither from a certain religious spirit nor from Armstrong’s feminist sensibility. Much of the acting is subpar, but that’s about the only blemish.

Don’t worry. One of these days I will also review the old George Cukor film of Little Women.