by Dean | Apr 2, 2019 | General

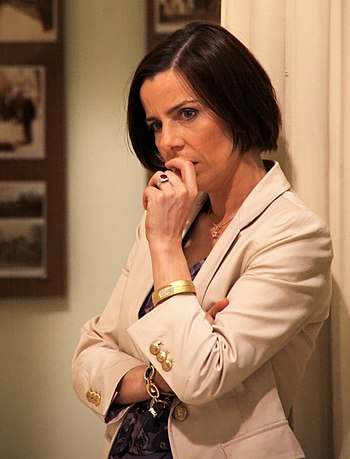

Ashley Bratcher displays realistic, suitable restraint and persuasive agony as Abby Johnson, a Planned Parenthood director (and real-life person). We miss her, in the faith-based Unplanned (2019), every time she is not on screen.

Whatever moral merit exists in Planned Parenthood—and filmmakers Chuck Konzelman and Cary Solomon do not believe there is very much—the movie is hot and bothered that bloody abortions are taking place in P.P.’s private rooms; and well it should be. Abby herself has had two abortions and scarcely cares that her Christian parents and her husband are offended by her director job. However, P.P.’s garbage, its evildoing, becomes too much for her. She actually seeks help from anti-abortion protesters.

Unplanned is a powerful film until its last twenty to twenty-five minutes. Then its artistry starts failing. There is not enough build-up to Abby’s decision to leave Planned Parenthood, and the script begins to propagandize for the pro-life movement. The movie ends up being less successful than Gosnell. But for a long time that artistry is there. And Bratcher’s performance is there. Final word: However much Pure Flix recoils from it, the movie’s R rating is justified.

by Dean | Mar 28, 2019 | General

The Nick Searcy (director)-Andrew Klavan (screenwriter) effort, Gosnell—about the infanticide in Dr. Kermit Gosnell’s Philadelphia abortion clinic—has its flaws. For one thing, Klavan’s dialogue is not masterly (sarcastically: “You’re a ray of sunshine”). But the film is intelligent middlebrow drama all the same, technically conventional but also brave and gripping. More gripping, I would say, in all its ugly clinic scenes than in the courtroom parts which supply the movie’s subtitle: The Trial of America’s Biggest Serial Killer. This is especially true when police officers and an assistant D.A. investigate, hardly believing what they see, said clinic. Dean Cain enacts one of the cops and is commandingly true. Sarah Jane Morris as the D.A. and Earl Billings as Gosnell are faultless.

by Dean | Mar 27, 2019 | General

Saturday Afternoon (1926), a silent Harry Langdon flick, is a little over 26 minutes long and un-tediously endearing. Langdon plays a mild-mannered gent married to a shrew (Alice Ward), probably because of which he agrees to join his portly pal (Vernon Dent) for an afternoon tryst with two lovely dames. Suspense builds as he tries to avoid his wife’s suspicions and animosity, but it’s not as though we actually sympathize with Harry: he’s a milksop who, inarguably, should have told the dames he is married. He also gets stupid with two other freewheeling young women and a brick he is holding. So it’s Harry, warts and all, and he soon takes a necessarily rough ride.

Competently directed by Harry Edwards, the film is funny without being too much, and Langdon is marvelous with his committed acting and man-child face and body activity. The other actors are good too. The best thing about the short script is its unpredictability.

Maybe, just maybe, Saturday Afternoon is art.

by Dean | Mar 22, 2019 | General

I haven’t been seeing very many current movies, and this even includes The Death of Stalin. But I did read the graphic novel, The Death of Stalin (2017), by writer Fabien Nura and artist Thierry Robin—it “inspired” the making of the movie—and I enjoyed it. The pictures are stark and tough-minded, the writing is magnetic.

The monstrous Stalin dies early on. The monstrous Lavrentiy Beria is first shown raping a hapless girl (for a rapist he was), and it isn’t long before we see just how contemptuous of Stalin the barbarous official is. After the big guy dies, Beria schemes. Depicted here is a cold hell, a bleak, loveless, secular domain where violence can be employed at any time and self-seeking dominates. When criminals are in power is the book’s theme, and it’s virtually relevant for the situation in socialist Venezuela when Madura blocks foreign aid from reaching his distressed people. I repeat: socialist Venezuela.

by Dean | Mar 20, 2019 | General

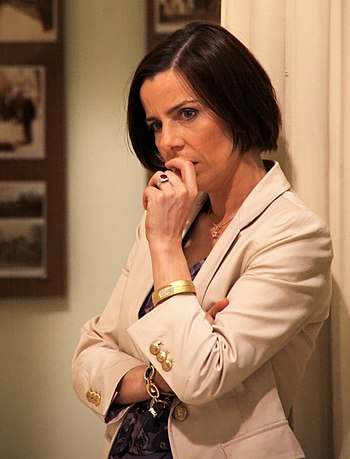

A Catholic nun-to-be, Ida (Agata Trzebuchowska), learns that she is Jewish and that her parents were murdered in an anti-Semitic Poland during WWII. The person who discloses this information is Ida’s aunt (Agata Kulesza), a disillusioned former state prosecutor for the Polish commies. . . This is all I wish to say about the plot of the well-received Ida (2014) since so many reviewers have already described it, so I will go on to pronounce it a solid work of art about which Peter Rainer is absolutely right in his view that the film is “about the spiritual agonies of postwar Poland.”

What’s more, it exhibits how people respond to the fragility of their own lives in a place like postwar Poland: Ida, after all, is quietly rattled by what she learns. Patently, there are good responses and bad responses.

Pawel Pawlikowsky, the man who directed the annoying (to me) and ignorant My Summer of Love, has acquitted himself nicely with Ida, a film of black-and-white pictorial benefits. I mean shots such as that of Ida standing in a circular, below-the-ground spot for which the clergy surely have a name and telling a statue of Jesus situated there that she’s not yet ready to take her vows. Or the one where, at a fork in the road, she kneels and prays before a station of the cross while her aunt waits beside her car and smokes. With images like these, the movie cannot escape providing at least hints of depth and significance.

(In Polish with English subtitles)

English: Agata Kulesza – a Polish actress. Busko-Zdrój, 30.06.2010 r. Polski: Agata Kulesza – polska aktorka na planie “Ojca Mateusza”. Busko-Zdrój, 30.06.2010 r. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

by Dean | Mar 16, 2019 | General

The nineteenth century in Stanley and Livingstone (1939) is much like the twentieth century in that the work that men do takes them far from home and into remote areas, and the men aren’t even soldiers. One of them, Dr. Livingstone (Sir Cedric Hardwicke), is a missionary who might have died in Africa, but didn’t. Henry Stanley (Spencer Tracy) is a newspaper man assigned to hunt down Livingstone if rumors of his death are false.

What would be corny in movies today, such as some stuff involving Walter Brennan, was not considered corny in 1939, although there is not that much corniness at all in this absorbing Henry King film. Much of it is quite mature (there is intelligent talk) and well-meaning, with some captivating, Kenya-provided safari footage. Even the less than believable hot pursuit of Stanley and his helpers, who have virtually no arms, by many hostile natives is something to see. As for the acting, a lot of grounded work gets done. Spencer Tracy is just Spencer Tracy—but this works. Hardwicke is truly fine as a man of God, while Brennan, Charles Coburn, Nancy Kelly and others are exactly right. Congrats all around.

by Dean | Mar 12, 2019 | General

In the 1932 Night World, there is an opening montage of night-life naughtiness wherein a shot of a young boy in prayer appears. If the boy is praying for the adults who frequent Happy’s Nightclub, they need it. Trouble, like depravity, rises in this spellbinding sphere; there is talk of hardship (Tim the doorman’s wife is in the hospital) and, later, more than talk. A fellow named Michael Rand (Lew Ayres) is getting drunk after the murder of his father, and he himself is almost murdered (!), for all the comfort he receives from Mae Clark‘s friendly dancer.

In large measure it is blackly realistic if dramatically lean. Richard Schayer did the screenplay, not at all flubbing the dialogue; and the appropriate direction is by Hobart Henley. As usual with early ’30s American flicks, though, an antiquated song and dance number gets performed, something Scorsese never had to put up with.

by Dean | Mar 10, 2019 | General

A melodrama of pain, disaster and love, D.W. Griffith‘s Way Down East (1920), a silent film, is an energetic attack on snobbery and hardheartedness.

Lillian Gish is quietly sensitive and moving as a country girl tricked into a false marriage by a wealthy womanizer, a caricature successfully played by Lowell Sherman. Griffith wonderfully cinematized a 19th century play by Lottie Blair Parker, with tragic moments involving the Gish character and humorous moments involving minor folks, not Gish, such as Seth and (repelling) Martha, with their farcical faces. The film has no epic scope, but it is a staggering production all the same.

by Dean | Mar 6, 2019 | General

A deaf married couple, Peter and Nita, resist the idea of providing their deaf little girl, Heather, with the cochlear implant she asks for. To Peter’s brother Chris and his wife Mari, both of whom can hear but who also have a deaf child, this is a form of abuse. They intend their baby son to receive an implant regardless of opposition from Mari’s deaf parents (that’s right: Mari has nonhearing parents AND a nonhearing son). The reason for Peter’s and Nita’s reluctance is that they don’t want Heather to miss out on the “deaf culture,” erected by the deaf community, they patently prize. Eventually Heather is affected enough by her parents’ opposition to say she doesn’t want the implant after all.

There are a lot of charming children in this documentary by Josh Aronson—titled Sound and Fury (2000)—but charming children is not what it’s about. It is about the fear of new technology, in this case fear issuing from those who have perforce understood deafness, not hearing, all their lives. Yet now they encounter something that may make deafness for the next generation extinct. Presumably it is also about selfishness, not to say possessiveness toward not only deaf culture but deafness as well. Sound and Fury is a revealing film. Aronson has a great subject—families and cochlear implants—about which he is a neutral observer. Nor does he use a narrator. Anyone interested at all in this New Millennium development and controversy ought to view this well-done, theatrically released documentary. You won’t find it uninvolving.

Postscript. Heather now has a cochlear implant.

Cover of Sound and Fury

by Dean | Mar 3, 2019 | General

A 1962 picture from France, Love on a Pillow is about self-destruction in the blood, and the far-reaching effect of erotic love. Genevieve (Brigitte Bardot) discovers a man who is attempting suicide and saves his life, later joining him in an amatory relationship. About this man, Renaud (Robert Hossein), it may be said, “Once a wreck, always a wreck.” He is a louse too, but Genevieve, a weak, complicated beauty, cannot leave him.

Sometimes rather dreary, the film is also sensual, usually smart, and imaginatively directed by Roger Vadim. For example, Genevieve and Renaud are arguing with each other as they approach their car, but since the camera is trained on the outside of the car, once the couple get in, the continued argument can no longer be heard. The audio is lifted.

The movie’s ending is bad—overblown—but the acting isn’t. Bardot does well enough, although her coldness is okay only up to a point. She needs to give us what someone like Monica Vitti does. Hossein, on the other hand, offers some depth and sophistication. So does Love on a Pillow (a.k.a. Le repos du guerrier), adapted from a novel by Christiane Rochefort. I’m glad it exists.